Updated January 28, 2025

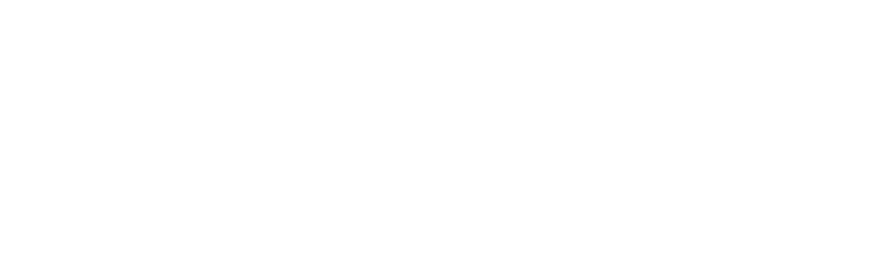

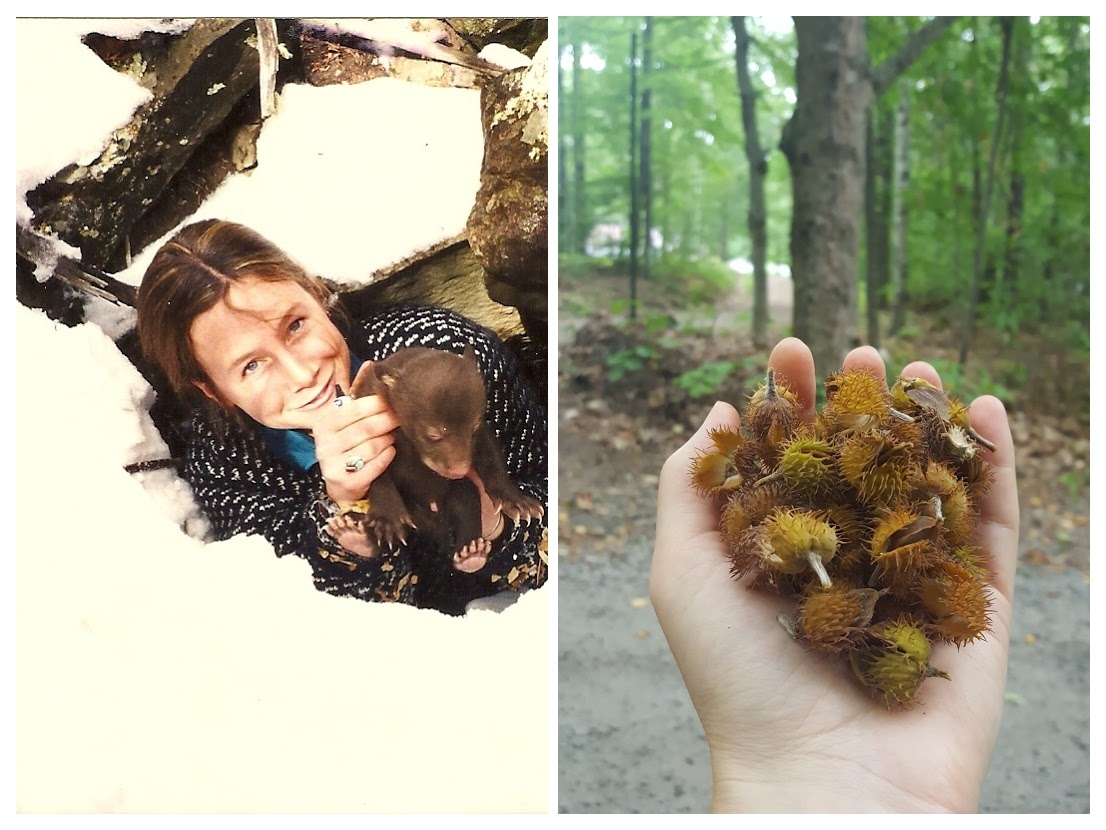

In the 1990s I worked on a number of black bear studies and visited winter dens to help collect reproductive and survival data (left); beechnuts gathered at the base of an old, gnarly tree near my home -this year is a big nut year (right)!

“I WAS IN PERPETUAL AWE OF THE QUIET MIRACLE OF HIBERNATION, OF MAMA BEAR NURSING HER CUBS THROUGH THE WINTER ON AN EMPTY STOMACH.”

I miss crawling into bear dens – that feeling of being in that deep, dark hole, all alone with mama bear and her cubs, in the dead of winter.

I remember it like it was yesterday, the sound of her slow heartbeat, the smell of cedar bark lining her bed, and the muffled voices of the rest of the bear crew, just outside the den entrance waiting for me to hand out the cubs.

I was in perpetual awe of the quiet miracle of hibernation, of mama bear nursing her cubs through the winter on an empty stomach.

Each time, I was flooded with an almost overwhelming sense of gratitude that I was able to witness - so intimately - one of the most evolutionarily successful survival strategies in nature.

What does this have to do with beechnuts?

You see, whenever I see beechnuts, I think of bears.

Weighing a 3-month old bear cub in the North Maine Woods.

Many years ago, I worked as a field biologist to gather important population data on black bears. We used radio-telemetry to locate collared females in their winter dens.

As the “den mole”, my job was to go in and fetch the cubs once mama was safely immobilized (with a tranquilizing drug administered by injection from the end of a syringe pole).

I worked for the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife on one of the longest running studies of black bears in the world. Such a long-running dataset is a treasure trove of information on black bear population ecology and dynamics.

Maine's biologists have been able to track about NINE generations of bears since 1975!

A key measure of the long-term health of a bear population is something called “recruitment” – meaning how many bears are being recruited into the population via reproduction.

During bear den visits we’d count, measure, and mark cubs and yearlings (cubs are born in the den in January and stay with the mother for about 18 months) and we’d also assess the health and condition of the mother.

Through this yearly process, female bears can be monitored for life – up to 30+ years – over which time a healthy female may have a dozen litters of cubs. Through this population monitoring the state biologists can estimate population size and track trends in different areas of the state.

This is where our superfood comes in – beechnuts!

Through the 1980s and 1990s (the latter decade being when I worked on the bear crew), Maine’s biologists observed a fascinating pattern of synchrony with beechnuts and bear cub production.

As with many nut and fruit crops, beech have heavy nut years, and other years where production is low. For the beech of northern Maine, the trees would produce a lot of nuts every other year. On a good nut year, bears were fat going into the dens. On alternating years when beechnuts were scarce, young females that were near breeding age (4-6 years old) would not be as fat going into the den and would not give birth to cubs (bears breed in June but do not become pregnant until many months later, and only if they are in good condition going into the den).

As a result, alternating years of nut-rich conditions were eventually reflected in the timing of cub litters – and the two were in synchrony.

To simplify a complicated phenomenon, let’s just say that for many years running most of the cubs in the northern Maine study area were born in the winter following a good beechnut year.

That pattern is no longer observed because beech have declined and bears enjoy a larger variety of food choices, making them less dependent on the fall beechnut crop.

Beechnuts remain an incredibly important, nutrient-dense food source for black bear, as well as for white-tailed deer, Wild Turkey, Ruffed Grouse, Wood Duck, woodpeckers, and more than a dozen other mammals and birds.

In our region overall, oak and beech are both important wildlife foods in the fall, but beech is much more valuable from a nutritional perspective.

Beechnuts have about twice as much protein and calories per edible portion as compared to acorns. That’s amazing, isn’t it?!

They really do pack a nutritional punch that can make a world of difference for wildlife as they go in to a harsh Maine winter.

For this reason, on behalf of woodland wildlife throughout Maine, I partner with forestland owners to help them promote groves of healthy beech (and oak) that will produce a high yield of beechnuts (and acorns).

How to Boost Beech, the Superfood in Your Autumn Landscape

1) Release healthy trees from competition.

Whether you have one beech tree or acres of them (every nut counts!), you can provide more sunlight, nutrients, and growing space for select trees to boost nut production, and provide for wildlife that are dependent on these fall foods for their survival. This takes expertise and knowledge of forestry and beech bark disease, thoughtful design, and careful management - but I can help!

2) Cut diseased trees for firewood!

While not considered a valuable tree by the timber industry (and in fact, a nuisance due to their aggressive regeneration), beech is an excellent firewood and will warm you four times: once while cutting it, once while splitting it, once while stacking it, and finally, when it’s burning in your woodstove or fireplace!

3) Share the knowledge - share this post.

Help educate your neighbors and our communities about the importance of beech as a wildlife superfood, and together we can bring back the big beautiful, smooth-barked beech that can feed wildlife for generations to come.

A bear-scarred “Super Beech” in Vermont (showing claw marks), regularly climbed by bears to feed on the nuts (left); an old, diseased beech that is nonetheless producing a huge nut crop this year (right).

Did you know? Beech bark disease is caused by the collaborative handiwork of two European imports, an insect and a fungus. Over the last 100+ years it has resulted in the large-scale decline of beech throughout New England, although some trees are resistant or tolerant. The old, lesioned beech tree in the photo above has withstood beech bark disease, ice storms, and more – yet this tough tree is producing a bounty of beechnuts this year (as evidenced by those collected in my hand in only a few minutes).

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE tips, tools, and insights for building habitat and hope.

#ThePersonalEcologist

I co-create biodiverse habitats with eco-minded stewards throughout the Northeast - at any scale.

I have 30 years of experience and a lifelong commitment to wildlife conservation.

Read My Story.

-

Deborah

Perkins

- Dec 22, 2023 Storm Habitat: Nurse Logs, Dens, and More

- Aug 8, 2023 Beautiful Buttonbush in Bloom

- Jun 17, 2023 Snapping Turtles on the Move

- Feb 1, 2023 The True Harbingers of Spring: Chickadees

- Mar 20, 2021 The Power of Photoperiod

- Feb 19, 2021 The Golden-crowned Kinglet: A Royally Charming Winter Resident

- Feb 8, 2021 Subnivean Secrets

- Jan 9, 2021 Wild Reads: Ravens in Winter

- Oct 23, 2020 Flower “Beds” for Bumble Bees

- Oct 4, 2020 Wise Oaks, Clever Jays

- Sep 11, 2020 Goldenrods: Top Plants for Boosting Biodiversity

- Aug 25, 2020 Gentle Golden Wasps Adorned with Pollen

- Aug 1, 2020 Water for Wildlife - Birdbath Basics & More

- Jul 19, 2020 Fruits of the Forest

- Jul 11, 2020 Hungry Little Hummingbirds

- Jun 24, 2020 Hatching Out: Mother Nature's "Escape Room"

- Jun 12, 2020 Maine's Real Lupine Revealed

- May 31, 2020 Wild Geranium in Flower

- May 24, 2020 Moosewood Chandeliers

- May 17, 2020 Shadbush in Bloom

- May 7, 2020 Native Nectar for Queen Bumble Bees

- Apr 25, 2020 Waves of Warblers

- Apr 19, 2020 Attracting Bluebirds without Boxes

- Apr 12, 2020 Hungry Bears on the Move

- Apr 5, 2020 Bees on Red Maple Flowers

- Mar 27, 2020 Sky Dancing

- Mar 22, 2020 Fox Kits Being Born

- Mar 15, 2020 Corvids a-Courtin’

- Mar 8, 2020 Phenology Notes: Witnessing The Seasons of our Wild World

- Feb 5, 2019 Plan Your Habitat Garden

- Jan 2, 2019 Wild Reads: We Took to The Woods

- Nov 28, 2018 Winterberry: The Gift that Keeps on Giving

- Aug 16, 2018 Where Have All the Whip-poor-wills Gone?

- Jun 22, 2018 Give a Warm Welcome to Wild Bees (Super-pollinators Part 2)

- May 16, 2018 The Wonder of Wild Bees (Super-pollinators Part 1)

- Apr 19, 2018 Saving Songbirds Starts with Your Morning Coffee

- Mar 21, 2018 Wildlife Habitat Design in A Wounded World

- Feb 16, 2018 “Intelligent Tinkering” - How to Boost Biodiversity at Home (Leopold’s Wise Words Part 2)

- Jan 18, 2018 Carnivore Coexistence (Leopold's Wise Words - Part 1)

- Dec 14, 2017 Dead and Dying Trees are Key to Life

- Nov 14, 2017 A Top Threat to Biodiversity: Invasive Plants

- Oct 18, 2017 Hallowed Habitat

- Sep 21, 2017 Beechnuts - Superfood for Bears & Other Wildlife

- Aug 22, 2017 Baby Bats Need Love Too

- Jul 25, 2017 Bring the Magic of Fireflies Back Home Again